New Perspectives

How Can I Be Sure?:

The Dialogue Between Painting and Photography in Modern and Contemporary Art

by Matthew Biro

Since the emergence of the first daguerreotypes and calotypes in the late 1830s, the relationship between painting and photography has been a complex one. On the one hand, photography was recognized to be an aid to painting—it was a tool for strengthening its naturalism and verisimilitude—at a time when painting was still understood to be a powerful means of moral and historical instruction. On the other hand, photography was from the beginning seen as painting’s intractable enemy: a soulless machine destined to destroy high art by usurping painting’s place in the public eye.

By providing information and entertainment in visual form, photography was thought to dull visual discretion and promote clichés: standard poses and costuming as well as “stock characters,” recognizable social or national stereotypes, often defined in terms of gender, race, class, nationality, or social or economic function. It could provide truth, clarity, and objectivity, but not “art,” in the sense of a creative transformation of the visual. Over the course of the nineteenth century, the initial fears about photography’s danger to painting seemed confirmed by the growth of a photo-illustrated popular culture—books and magazines—and, later on, after 1895, the motion picture industry. Lens-based news and entertainment created a new mass audience that dwarfed the bourgeois audience for “fine” or “high” art, and painting’s primacy—its claim to be the richest and most complex medium of visual communication—was cast more and more into doubt. Painters, as a result, felt compelled to distinguish their representations from photography, which was associated with non-artistic qualities, such as dispassionate documentation and melodramatic narrative. This is one of the reasons that the academic realism of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries lost its dominance, and advanced painting became increasingly abstract over the course of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, developing a “modernist” focus on its material properties to the exclusion of its depictive functions. In response to photography, modern artists made painting flatter and less mimetic, more self-referential, and increasingly focused on its own history.

Although it has taken many different forms over the course of its long existence since the nineteenth century, modernism in painting generally emphasizes either the subjectivity of the author and spectator or the materiality and phenomenal presence of the work. Sometimes, it does both at the same time. In earlier modes like Impressionism and Expressionism, it celebrated a connection or shared sensibility between artist and audience—an alternative “point of view,” often understood as anti-bourgeois or bohemian, that was a negation of the commonly understood physical and social world. It was created and appreciated, in other words, as revolutionary way of seeing, a more truthful optical experience discovered beneath the stereotypes and conventions that distorted everyday modes of perception. In other more recent forms, particularly after the breakthrough to complete abstraction around 1912, modernist painting has focused on its own forms, materials, and techniques to the exclusion of the world, a self-reflexivity that can be seen in the works of numerous artists on both sides of the Atlantic. Manierre Dawson’s 1913 oil on canvas, Essnzee, exemplifies this early abstract tendency in the United States. As Dawson expressed in his journal at the time, such non-objective works were not intended to represent the external world, but the internal reality of the painting itself: “It exists nowhere else.”[1] The truth of a painting, the source of its optical certainty, became its phenomenal presence, which was understood to be the product of its formal interrelationships, its materiality and processes of making, and the conversation it created between the artist, spectator, environment, and historical tradition.

As a mode of advanced art, modernist painting was first successfully challenged by photography in the 1920s, when abstraction began to be criticized for its disconnection from everyday life. The academic hierarchy of the fine arts, which placed painting and sculpture at the pinnacle, was disrupted, as avant-garde artists like the Dadaists, Constructivists, and Surrealists sought to make contact not just with elite beholders but also with a modern mass audience. Now all media were equal in the service of radical art; the truth of the work was a result of its criticism of the world; and the concept behind the work’s production grew in importance. Many artists in the Dada, Constructivist, and the Surrealists movements liked to double or superimpose images as a way of making them allegorical or uncanny, thus challenging the status quo; and reproductive media like photography and film were particularly well suited for this practice of replication. Moreover, as suggested by Salvador Dalí’s Double Image, 1965, a watercolor and ink on paper, even when the avant-garde artists used more traditional media, a photographic aesthetic prevailed. The central set of forms read as a portrait bust of Voltaire looking to his right as well as a grouping of four or five female figures—the philosopher’s eyes and face are constituted by the two left-most women. The figures evoke preexisting source material taken from the mass media, perhaps fashion magazines or art books, as well as printed money. And in this way Dalí’s watercolor foregrounds the fundamental acts of copying and multiplying inherent in photographic practices and the massive proliferation of visual spectacle that photography has produced since the nineteenth century. Its truth does not lie in the painter’s hand or the uniqueness of his vision, but rather in the work’s social-psychological criticism (what Dalí called his “paranoiac-critical method”): the way Double Image disrupts our everyday understanding of reality, suggesting that we live in a world in which nothing is original and where—because of the social, psychological, and technological structures into which we are born—everything can be transformed into something else.

Although advanced painting lost a certain priority in the 1920s and 1930s, it did not fade away; rather, it retained a powerful attraction for both critics and the popular audience. Indeed, what is striking about contemporary art since the middle of the twentieth century is how much art’s development enacts a cyclical struggle between the two media, the fine art fortunes of painting and photography rising or falling in relation to one another. Each medium, moreover, has, since that time, come to explore itself more and more in relation to its (photographic or painterly) “other.” In the United States and Europe, for example, forms of abstract painting triumphed after the end of World War II in apparent opposition to the historical avant-garde of the 1920s and 1930s as well as the realist tradition that remained in painting. With its play between organic and hard-edged forms, Jack Youngerman’s South, 1959, for example, shows how complex and convincing complete abstraction in painting could remain long after the high point of Abstract Expressionism. The truth of the painting here is a unique mixture of (objective) phenomenal presence and (subjective) composition and color choice. Then, in the 1960s, abstraction in painting was partially challenged by the rise of photographically-engaged Pop art on both sides of the Atlantic; and, in the diverse and pluralistic 1970s, both representational and abstract avenues were pursued. Roger Brown’s Jacknife, 1975, a quasi-comic depiction of a truck accident, shows how multifaceted representational painting could be in the 1970s. Playing between painting, sculpture, and cinema (because of its sequential imagery), it mixes multiple stylistic sources as a way of criticizing the human condition in the modern world. What did change since the 1960s is not the fact that painting and photography are engaged with one another, but rather the density and plurality of their interconnections. Likewise, and despite what critics say to the contrary, no medium has ever been fully dominant again since the mid-century.

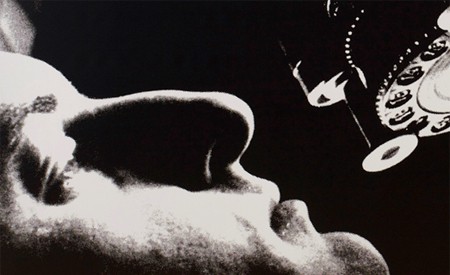

The Hallmark Art Collection is particularly rich when it comes to documenting the evolving conversation between painting and photography in contemporary art. With the popularity of postmodern photography in the United States in the 1980s and 1990s, photography seemed to eclipse painting as the preeminent art form. Barbara Kruger’s Untitled (A picture is worth more than a thousand words), 1992, is an iconic example. A photographic silkscreen on vinyl that has been blown up to the size of a painting and surrounded by a red border, it presents a close-up, black-and-white image of a film editor, making a cut with his scissors, while holding the celluloid motion picture strip up to his eyes. The face of the film editor almost touches the celluloid “dream factory” object that he clutches, emphasizing the erotic charge that mass media technologies have for the contemporary spectator. He is caught in the act of making a cut, an action that reminds the viewer that photographic representations are shaped, abstracted, and potentially misleading. Finally, the title, in conjunction with the visual elements, is self-reflexive. It invites the audience to think about how the power of communication has grown radically with the rise of lens-based media.

In the postmodern art discourse of the time, photography was seen to be inherently more critical than either painting or sculpture, which, critics claimed, had largely become commodified and exhausted, as well as disconnected from the contemporary moment. By isolating, cropping, enlarging, juxtaposing, and recontextualizing advertising images, and then superimposing critical titles and epigrams, Kruger spoke to the suspicions and concerns of her time, its paranoia about how the mass media and entertainment industries served both capital and the state. By making the mass media strange, Kruger’s postmodern photographs criticize their contemporary world, disclosing its ideologies and the ways in which its culture industries construct different types of social and “personal” identity. Foregrounding questions of history and mass reproduction, postmodern photographers like Kruger fulfilled their contemporary audiences’ desire for art with political relevance and with a critical perspective on the contemporary moment. This criticality was shared by painters of the era, such as Julia Wachtel—another artist of the Pictures Generation—who appropriated journalistic photography in her mixed media canvases to similar effect.

In addition to focusing on history, identity, politics, and the media, postmodern photography was thought to be critical because it undermined traditional aesthetic qualities—immanence, autonomy, presence, originality, and authorship—that certain critics of the time associated with the modern tradition of painting and sculpture. The photograph was mechanical; it resisted the handmade and the subjective; and it could be infinitely copied. In addition, it was indexical, a direct trace of something objective, and thus “unconscious” and “anti-subjective” in important ways, produced by the world as much as by the photographer. Through these qualities, postmodern photography distinguished itself from the elite bourgeois art of the past as well as modernism, which, the postmodern photograph demonstrated, retained many bourgeois values.

Vik Muniz’s After Motherwell (Pictures of Ink), 2002, exemplifies this postmodern critique of modernist aesthetics in a particularly convincing and powerful way. A series of eight Iris prints with varnish, it depicts enlarged hand-made copies of portions of Robert Motherwell’s abstract expressionist paintings. Created in thick ink and photographed while still wet, the abstract forms seem oddly artificial. Blown up, fragmented, and rendered almost three dimensional, they undermine the supposed immediacy of the original gesture—Motherwell’s subjective mark—through copying and by setting up a comparison between the uniqueness of painting and the reproducibility of photography. In this way, a multitude of questions are raised about the nature of art, originality, visual representation, and perception in general. In addition, Muniz’s After Motherwell series also reminds the spectator of the immediate history of its guiding idea, namely the Pop artists’ critique of Abstract Expressionism. Roy Lichtenstein’s iconic Pop screenprint Brushstrokes (1967) parodies the reverence that the Abstract Expressionists and their critics had for the abstract painterly gesture by giving the painter’s mark a comic book form. Transforming the expressionist gesture through photomechanical reproduction (as suggested by the Ben Day dots that are signs of the halftone printing process used in mass market magazines and comic books), it suggests that even the most intimate expressions of the human soul can be turned into stereotypes through their citation and reproduction. And by also reminding us of the Pop critique of painting, Muniz’s postmodern photographs reveal the density of the history with which they engage.

Conceptual artists in the 1980s and 1990s showed great affinities with the postmodern photographers, exploring painting and other traditional media in photographic ways and as constituent parts of broader social and economic systems. Allan McCollum’s Five Colored Surrogates, 1987, is a good case in point. An assembly of five schematic paintings in four different sizes and five distinct colors, it is inherently photographic in that all of the works are cast from molds taken from “originals” crafted in wood and cardboard. Like photographs, McCollum’s “paintings” are traces or indexes of something real. Moreover, although all are slightly different from one another, the surrogates seem more like machine-produced products than unique and auratic works of art. In addition, as schematic representations of typical paintings, consisting of a frame, matte (or mount), and “picture,” the works redirect the beholder’s attention to the physical and social context in which the paintings existed and functioned. McCollum used this strategy to provoke his audiences to think about the role of painting as a signifier of status and elite belonging as well as the value systems promulgated by galleries and museums exhibiting modern art. For him, the truth of painting became its ability to reveal institutional structures and social functions.

By taking a high art medium and making it infinitely reproducible, McCollum, like Lichtenstein in the 1960s and Muniz in the 2000s, attacked the presumed subjectivity behind modernist painting. In their work the important modernist distinction between original and copy breaks down. Likewise, as a schematic accumulation of paintings that nonetheless contains no images, Five Colored Surrogates plays between representation and abstraction, confounding another category distinction that high modernism sought to maintain. The works by Lichtenstein and Muniz discussed above also engage in this critical dismantling, suggesting that realist depiction and pure nonobjecivity are not as distinct as they originally seemed to be. Thus, as demonstrated by all three artists, photography and references to photographic processes have been used consistently over the course of the second half of the twentieth century to counter the claims of high modernist painting.

Even in more traditional forms of postmodern painting in the 1980s and 1990s, photography played a key role. David Wojnarowicz was an activist artist who worked in a variety of different media including drawing, photography, and sculpture, as well as text and performance, installations, street art (stencils and murals), and even video and film. Many of his paintings include actual photographs or photographic reproductions excised from books and magazines. Wojnarowicz’s Biography of Peter Hujar (7 Miles a Second), 1988-1989, for example, appropriates black-and-white images that appear drawn rather than photographed. At the same, because of their naturalistic illustrational style, they point to the photographically-produced mass culture that increasingly defined Wojnarowicz’s contemporary world.

The painting commemorates Wojnarowicz’s lover and mentor, the photographer Peter Hujar, who died from complications arising from AIDS in 1987. (Less than a year later, Wojnarowicz was himself discovered to be HIV positive; he died in 1992.) Against an indistinct blue background, which could suggest an agitated cloudy sky or some organic surface viewed through a microscope, Wojnarowicz juxtaposes a fragmented image of a reclining man, emblematic of his dying lover, with a mathematical equation, which signifies the speed that a particle must obtain in order to escape the earth’s gravitational pull. Evoking the science and medicine that failed Hujar, the equation also serves as a metaphor, drawn from astrophysics, for mortality and the possibilities of its transcendence. An angular red lattice surrounds these fragments and links them to a series of circular insets, which include incomplete illustrations of a speeding locomotive, an architectural ruin, a Tyrannosaurus Rex, an ant crawling over oval forms, cellular imagery, and an active volcano.

Keenly aware of his life-long position outside mainstream American society—first as an abuse victim and child prostitute and then as a gay and (most recently) HIV positive man—Wojnarowicz used photographs and mass media illustrations to represent and comment upon the “pre-invented” world and categories into which he was born, yet believed he never really fit. Employing the circular inset to suggest technological mediation—the form suggests both a telescope, a microscope, and a surveillance camera—he surrounds his lover with a cluster of clichéd images, which, through their fragmentation and incongruous connections with one another, suggest a poetic and non-normative re-envisioning of Hujar’s life story. “Peter,” Wojnarowicz, recalled, “had a habit of recreating his biography each time his photographic work was included in another book or anthology.”[2] In his painting, Wojnarowicz repeats Hujar’s process of self-reinvention, representing the photographer’s half-real, half-fictitious personal mythology through ambiguous fragments appropriated from the common culture. Nature mixes with technology as different species and time periods collide. Combining the personal motifs particular to Hujar with history, politics, and myth, Wojnarowicz’s photographically-engaged painting evokes the AIDS crisis, with its governmental inactivity, religious intolerance, and homophobia. But, through its surreal juxtapositions, it also critically suggests that the traditional conceptual structures that subtend our mass-mediated existences can also be overcome, and that in their place, new relationships between people and their societies may arise.

As suggested by Wojnarowicz as well as the other artists in the Hallmark Collection discussed above, the relationship between photography and painting has always been a multifaceted one. And in recent years, the creative dialogue between these two modes of visual representation has only gotten more densely interconnected—something that has benefitted both media. Time and time again, succeeding generations of artists have discovered new meaning and inspiration in each medium through combining processes, recontextualizing elements, or by reinterpreting the specific properties inherent in each mode. In all cases, however, the ultimate result has not been the absolute triumph of one medium over the other, but rather their mutual enrichment and further interconnection.

The dialogue between painting and photography has often centered on a quest for certainty, a search for the “truth” of visual perception. By challenging one another, each medium proposed different and evolving concepts of visual fidelity, variously understood as a mixture of subjective and objective—as well as individual and social—elements. Today, artists must also contend with the digital filter that further confuses the distinction between mimesis and invention that was once thought to distinguish photography from painting. And this engagement with the digital, which we see powerfully enacted in the recent work of Jason Salavon and Benjamin Edwards, among others in this collection, provides much cause for excitement in the contemporary moment.

[1] Ploog, Randy and Bairstow, Myra. Manierre Dawson, A Catalogue Raisonné, Published by The Three Graces in association with Hollis Taggart Galleries, New York, 322.

[2] Wojnarowicz, David and Guatarri, Felix, In the Shadow of Forward Motion, self-published in collaboration with PPOW Gallery, New York, 1989, unpaginated.